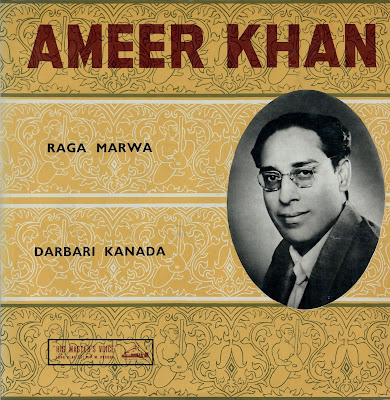

We start now to post a number of recordings by the great Ustad Amir Khan. Here his very first LP, the third LP of classical Indian music released by the Gramophone Company of India.

I bought it in the first half of the 1970s in the HMV shop on Oxford Street in London. I never had seen before so many LPs from India. I spend all my money there. If I remember correctly I bought about 20 LPs. Many of them vocal music by artists I only had read about till then and saw there for the first time LPs by them. Only the following year I made it to Southall, a small town next to London with a mostly Indian and Pakistani population. In Southall there were 3 or 4 Indian-Pakistani record shops and that was then even more paradise for a collector.

On the artist see the two articles below and these links:

From: Great Masters of Hindustani Music by Susheela Misra.

Ustad Amir Khan by Susheela Misra

Fourteenth February 1974 was an ill-fated day for Hindustani music because it lost two great stalwarts on the same day. Pt. Srikrishna Narayan Ratanjankar succumbed to protracted illness. Ustad Amir Khan in the height of his form and fame, was tragically killed in a car accident. Although in his early sixties the Ustad was still a force to reckon with in North Indian music, and had it not been for that grievous accident, he might have easily gone on dominating the music world for another decade or so. The world of Indian music went into mourning on l3th February 1974, and there were public condolence-meetings in numerous cities. Programmes of tributes to the two departed maestros were broadcast from all the important Stations of All India Radio.

Born in April 1912 in Kalanaur, Amir Khan began his musical training as a Sarangi- disciple of his own father Ustad Shahmir Khan, a noted Sarangi player who had learnt his art from Chajju Khan and Nazir Khan of the Bhindibazar gharana. Amir Khan’s early grooming in Sarangi was only the foundation of his musical edifice. He had a vision and imagination of his own for higher artistic flights. Being a reputed artiste and a warm friendly person, Shahmir Khan’s hospitable home was a veritable rendezvous of many great contemporary maestros like Ustads Allabande Khan, Jafruddin, Nasiruddin Khan, Beenkar Wahid Khan, Rajab Ali Khan, Hafeez Khan, Sarangi- nawaz Bundu Khan, Beenkar Murad Khan and several others. Thus, although Amir Khans’s early musical training commenced with Sarangi, the impressionable and intelligent youngster was constantly exposed to the various vocal gharanas of the times. Gradually, Shahmir Khan himself began to devote more time to Amir Khan’s vocal training in which merukhand (or Khandmeru) practice and sargam-singing were specially emphasised. Moulded by the styles of three great giants of his younger days, namely, Ustads Bahre Wahid Khan, Rajab Ali Khan and Aman Ali Khan, Amir Khan evolved his own stylistic school which came to be known as “the Indore Gharana.”

In fact, Amir Khan was a self-taught musician. He assimilated the distinctive features of the gayakis that appealed to his aesthetic sense and were in perfect accord with his voice. The style that he evolved was a unique fusion of intellect and emotion, of technique and temperament, of talent and imagination. His style was a synthesis of three different styles. He assimilated the colour and spirit of Wahid Khan’s style, (with its chastity of swara intonation and a richly soporific effect of melodic elaboration) so well that Ustad Wahid Khan blessed him. “Long shall my music live in you after I am gone”. The slow Khayal is rendered in such a slow tempo that it has “the langour of unfinished sleep.” This style originated in the Merukhand style of the Bhindibazar-gharana. This generally strove to produce the permutations and combinations of a given set of notes. These are like mathematical exercises with little artistic effect in a concert. The development of the Vilambit Khayal was marked by deep serenity. The concept of an extra slow tempo with a slow and meticulous unfolding of the raga and the “cheez” was taken from Ustad Bahere Wahid Khan. His taans were clearly influenced by the eloquent ones of Ustad Rajab Ali Khan. In sargam-singing, he revealed his admiration for Ustad Aman Ali Khan. During his early sojourn in Bombay, Amir Khan had be come a close friend of Late Aman Ali Khan. Amir Khan always maintained that had Aman Ali Khan lived longer he would have been the former’s “confrere in the world of music”. This newly amalgamated “Indore” style of Ustad Amir Khan captivated and influenced a whole generation of younger musicians of all categories through the contemplative and reposeful beauty of his slow, leisurely Badhat (elaboration) enlivened by the “exuberance of his proliferating sargams” and rushing taans. So tremendous has been the impact of his distinctive “gayaki” on the rising generation of young Hindustani vocalists that Amir Khan commanded a large following among the younger aspirants. He no longer remained as an isolated individual.

For years, he remained one of the most sought after classical vocalists of his times. What set him apart from his contemporary artistes was the fact that he never made any concessions to popular tastes, but always stuck to his pure, almost puritanical, highbrow style. “His music combined the massive dignity of Dhruvpad with the ornate vividness of Khayal”. There are some musicians of the Kirana school who argue that the words of the Khayals are of no importance ! But Amir Khan held different views. He used to say: “The poetic element in Khayal is as vital as its melodic element. An artiste has to have a poet’s imagination to be a good musician”. Amir Khan has proved that “chaste refined music does not lack listener-response”, for, he strictly remained uncontaminated by the present craze for showiness. The tall, handsome Ustad had a dignified concert presence. His dignity of bearing and his posture of Yogic calm on the stage struck a perfect accord with the serene grandeur of his music. It was as though his musical thought was in tune with some ideal of beauty and he was striving to communicate it to his charmed audience”. As Prof Sushil Kumar Saxena wrote (in the Sangeet Natak Akademy Journal 31) “An Amir Khan swara was at once a tuning of the self, a calm that spreads while Ghulam Ali’s glows with a pulpy luminosity.”

Amir Khan’s forte was the exaggeratedly slow or ati vilambit Khayal which he developed in a most leisurely mood with deep serenity and contemplativeness. While his ardent admirers found this part of his concert absolutely engrossing, there were others who found it “excruciatingly slow” or even “insipid”! He always avoided Sarangi accompaniment, and wanted nothing more than a steady, plain Theka from his Tabla accompanist. His favourite slow talas were Jhoomra and Tilwada. Words were subservient to the “absolute music” that he sang, and naturally, “bol-alaps” and “Bol taans” were conspicuously absent in his singing. In the course of his prolonged unfoldment of the vilambit Khayal asthayi, Amir Khan would sometimes render flashing “meteoric taans”. His “taans” were marked by many graces like elegant gamaks, lahak and clear “daanas” (clarity of each note). It was natural that the Ustad always chose highly serious, expansive, traditional ragas like Todi, Bhairav, Lalit, Marwa, Puriya, Malkauns, Kedara, Darbari, Multani, Poorvi, Abhogi, Chandrakauns and so on. Even the lighter ragas like Hamsadhwani acquired a serious expansive mood when rendered by Amir Khan. His rich, mellow voice was at its best in the deep, dignified “mandra” notes (lower notes). His voice had some inherent limitations, but he shrewdly evolved a style to suit his voice.

Summing up the essence of his father’s vocal style, Ekram Ahmad Khan (the eldest son of the Ustad) wrote: “Amongst the elder maestros of music, Khan Saheb was intensely devoted to Rajab Ali Khan of Dewas, and Aman Ali Khan of Bhindibazar. He also studied the styles of Bahere Wahid Khan and Abdul Karim Khan and amalgamated the essence of the styles of these four maestros with his own intellectual approach to music, and conceived what is now known as the Indore gharana of music”.

During the first 25 years of his life, Amir Khan devoted considerable time to sargam- singing, what is known as “Merukhand practice” consisting of varied permutations and combinations of kaleidoscopic swara-patterns. These complicated “Khandameru” sargams, and flashing meteoric taans brightened his reposeful vilambit Khayals now and then. The ”Merukhand” style of singing is mentioned in the l4th century Sanskrit classic Sangeeta-ratnakara of Sarangdeva.

Another significant aspect of Amir Khan’s art imparting it a unique quality, was his refined voice and the way he moulded it to suit his chosen style. Endowed with the face of an intellectual, his temperament, like his music, was serene, unruffled. He never lost his temper. He extended the same courtesy to all, big and small, and listened attentively to even lesser artistes. Humility was native to him, his judgements were generous, and he was above petty jealousies.

Although Amir Khan never rendered Thumris in his concerts, his disciples speak of the exquisite way in which he rendered Thumris for them in his intimate home-circle. His “cultured” voice was suited for the melodious Thumri style also. Amir Khan’s sole concession to the speed-loving contemporary listeners was the Tarana in which he did considerable research. According to him, the Tarana-syllables have a mystical significance. Although his voice was at its best in the lower notes, it could also soar and sweep across far-off swaras with nimble grace. Such was the influence of his music that in an era of impatient listeners, Ustad Amir Khan was able to instil, by the example of his own art, a genuine and widespread love for serious, contemplative music into the hearts of young music lovers all over the country. He was strongly against the idea of any short-cuts to success in music.

Even when Amir Khan did playback singing for some films, he refused to cut adrift from his classical moorings. The songs he rendered were always in highly classical style and in ragas like Darbari, Adana, Megh, Desi, Puriya Dhanasri etc. In his tribute to the Ustad, Prof S.K. Saxena writes in the Sangeet Natak Akademi Journal: “Amir Khan was different and solitary because of his absolute indifference to the reactions of his audience while he was singing. He never seemed to make a conscious endeavour to please the audience. He faced them majestically, with his music alone, and with pure classicality. Often his music seemed strangely disembodied from raga-tala distinctions into a kind of musical incense borne aloft on the very wings of devotion. His music, at its best, was rarely a dazzle. It would be rather an influence, an atmosphere which would just be with us till long after the recital”.

There was a time when Amir Khan was a rage in Calcutta and no music conference there was complete without his recital. The Films Division of the Government of India has brought out a documentary film on his life in recognition of his great contribution to Hindustani music. For his eminence as a performing artiste and for his significant contributions to classical music, he was crowned with many honours such as the Fellowship of the Sangeet Natak Akademi, the Presidential Award, Padma Bhushan (1971) and the Swar Vilas from Sur Singar Samsad (1971). But these honours and his large following in the music world left him untouched. Amir Khan continued to be a very simple individual “accessible to all and sundry”, and he never assumed any airs like some of his contemporaries. Though not educated in the formal sense, he was a highly sophisticated person who moved with dignity in the highest society where he was genuinely revered. It was considered a privilege to be his friend. Through his own efforts, he learnt Hindi, Urdu, Persian and a bit of Sanskrit, and he studied the writings of Guru Nanak, Vivekananda, Ramakrishna Paramahamsa and others. Khan Saheb’s son Ekram Ahmad Khan writes that it was these studies and his close friendship with Narayan Swami (of Calcutta) that led to his unique blend of Sufism. “Khan Saheb”, writes his son, “was a Sufi in the true sense of the word - a man without any specific religious ties, a man totally devoted to the oneness of mankind, a true citizen of the World”. Amir Khan was a good composer and some of his compositions reflect these religious convictions of his. One instance is “Laaj rakh lijyo mori, Saheb, Sattar, Nirankar, Jai ke Daata, Tu Raheem Ram Teri maaya aparampar, Mohe tore karam pe aadhar Jag ke daata.” Whenever I heard Amir Khan singing the Khayal in Bairagi beginning with the words “Man sumirat nis din tumharo naam”, I felt that the words and the spirit of the raga were most aptly suited for Amir Khan’s musical temperament.

Since 1968, Khan Saheb used to go to U.S.A in alternate years to spend the summer with his son Ekram Ahmad Khan, a graduate in chemical engineering from McGill University who has settled down in U.S.A as an Engineering Manager in Canada. [Sounds odd, doesn’t it? Maybe he lives in Buffalo and drives to Toronto for work:-). I wonder where Ekram is today and if he has any private unissued recordings of the Khansaheb – RP] Amir Khan also used to go as a visiting professor of music at the State University of New York at New Paltz where “he planted not only the seeds of his music among the students, but also left behind the legacy of his Sufi philosophy”.

Unassuming in his ways, Amir Khan had the capacity to adjust himself perfectly to his environments. He seemed equally at home among the humble as well as among the highly sophisticated. What a pity that this great artiste was snatched away in the peak of his career! Here was a rare classicist who sustained his art by pure devotion, and yet enjoyed wide popularity. Even now, more than 7 years after his untimely death, Amir Khan’s music is still a living force because his voice is being frequently heard over AIR through his recordings in the Archives and his Long Playing Records. The Indore gharana of Amir Khan continues to live on through his pupils like Amarnath, Kanan, Srikant Bakre, Singh Brothers, Kankana Banerji, Poorabi Mukherji and others. There are many others whose singing has been obviously coloured by the style of Amir Khan. The singer is gone, but his music is still with us.

*****

USTAD AMIR KHAN by G.N. Joshi

The death of Ustad Amir Khan in a tragic motor accident in Calcutta a few years ago has created a void in the world of Hindustani classical music. At the present time, when there is a dearth of such gifted artists, his death is an irreparable loss. Had he lived longer he would have had, at least, a number of able and talented disciples to carry on the tradition of his gharana.

In the last 25 years some artists have, by their revolutionary spirit, progressive outlook and creative faculties brought about radical changes in the style of presentation of classical music. Ustad Amir Khan was such an artist. Like Kumar Gandharva. Amir Khan disregarded the age-old, conventional traditions, and with his intelligence and talent evolved an entirely original style of presentation. He also succeeded in gaining the approval and recognition of critics and connoisseurs.

Amir Khan was born at Indore in 1912. Music was in his blood; his ancestors had been musicians in the Mughal courts. His father was an expert sarangi and veena player. A mehfil of Amir Khan’s was always a pleasant experience. He had a very impressive and magnetic personality. At his concerts he would always sit in the posture of a yogi doing his tapasya, with closed eyes and deep meditation. He maintained the same position till the end of his concert. His smiling countenance, a total lack of gesticulation or facial distortion, his absolute concentration on the song, and the slow, gradual build-up of a raga picture invariably kept his audience completely engrossed. He had, for accompaniment, two tanpuras tuned to perfection, a subdued harmonium and a tabla with a straight, simple but steady laya. An atmosphere of solemnity and tranquillity pervaded his concerts, in striking contrast with the noisy and sometimes unmusical gymnastic bouts some singers have with the tabla players that entertain listeners with acrobatics rather than providing them with aesthetic delight.

He had cultivated his voice till it was as exquisitely chiselled as a piece of sculpture. While presenting a raga he unfolded it with extreme skill, delicacy and purity. At times, when an ascending note appeared to be suspended in mid-air, he unexpectedly made a lightning play on that note, holding the audience spellbound. Because of his inborn, instinctive knowledge of avakash, kal and laya he was able to make his voice sound as if he was singing swaras from two different octaves simultaneously, treating his audience to a unique celestial experience. His mastery over layakari and the swaras was complete. His taans though complicated, and full of artistic twists, were executed in an easy and graceful way. He had an amazingly wide range of pitch, and he moved majestically through this span with his liquid golden voice. Listeners were always favourably impressed by his gayaki and skilled display of tonal beauty. He did not agree with the popular notion that the tarana was just a tongue-twisting exercise with a meaningless cluster of words, involving a lot of vocal jugglery in an ever-increasing tempo. He always put into a tarana a Persian couplet interwoven in the apparently meaningless ‘Dir tun, tan, din yalali, yalallum’, and honestly believed that these syllables did have some mysterious and mystic import. According to him it was the Persian scholar Amir Khusro who invented the tarana. Amir Khan was very keen on establishing this theory by carrying out research to unravel the hidden meanings of the tarana. But cruel destiny snatched him away and his mission was left unaccomplished.

Amir Khan’s presentation was always thoughtful and methodical and he rarely indulged in repetitive phrases. The thorough treatment he gave each raga naturally required considerable time for flawless elaboration. It was well-nigh impossible to get a satisfactory exposition from him in just 3 minutes. It was therefore only in the late 1960s that I could have him to record for a long-playing disc (in effect, it must have been in the late 1950s and the recordings in question are the ones we post here on his very first LP). It was not an easy job to bring him before the mike, though obtaining his consent was not all that difficult. Even to approach him posed a very big problem for me. Amir Khan lived, in those days, in very disreputable surroundings, where it was considered very objectionable for any gentleman to go, even during the day. This is the locality a little beyond and opposite the Congress House on Vallabhhhai Patel Road, near the Kennedy bridge. It is inhabited by professional singing and dancing girls, as well as prostitutes. Amir Khan was giving tuitions to some of these singing girls for his living and therefore had to stay in one of the buildings on the third floor. Later, when his financial position improved, he shifted to a flat on Peddar Road. Just beyond the building where Amir Khan lived was the residence of an elderly singer by the name of Gangabai. Ustad Bade Gulam Ali Khan and Ahmad Jan Tirakhwa often stayed with her. This shows that even women of these professions were treated with respect as artists, in artistic cirles. As the recording executive of H.M.V. I had to contact artists regardless of time and place.

To obtain Amir Khan’s agreement for the recording I had to meet him, and, therefore it was incumbent on me to visit his residence. I was greatly put off when I learnt about the locality where he stayed. I was afraid of what people would say if they observed me entering a house of ill repute. Any outsider would naturally draw his own conclusions, not knowing that an eminent singer was living in that building. If I had, out of fear of social stigma, refrained from going to visit Amir Khan, his great artistry would have gone unrecorded. The idea of securing his consent for recording together with a keen sense of duty prompted me to enter the building, eyes downcast, not looking about me till I entered Amir Khan’s room on the 3rd floor. Once in his room I cheered up, and I talked to him for an hour or two. After that I visited him often. We exchanged views on music and gharanas, and such visits gave me opportunities to study his likes and dislikes. These visits also gave him confidence in me. After a couple of months and 4 or 5 such visits, he agreed to come for a recording. Some more time was lost in persuading him to agree to the terms of payment. Finally this hurdle too was crossed. Yet Amir Khan went on cancelling dates, giving fresh ones and then again postponing the recording on some flimsy ground. I got fed up with his dilly-dallying and, in spite of my great regard and respect for him, I justifiably felt very annoyed. Ultimately one day I plucked up my courage and said to him, ‘If I had approached God Almighty as many times as I have come to you, he would have blessed me, but all I can get from you is the promise of a future date.’

Seeing my exasperation he became thoughtful, smiled a little and replied, ‘Please do not disbelieve me. Name any day of this week and I will keep the appointment.’ True to his word he came on the day I named, and I got from him his first long-playing disc. His favourite ragas were Marwa, Darbari Kanada and Malkauns. It is indeed rare these days to hear Raga Marwa as it was presented by Bade Gulam Ali and Amir Khan. His first LP was received with tremendous enthusiasm by the public. This delighted Amir Khan, and he was more than ready for another recording. In spite of this I had to put in a lot of effort and time to bring him to the studio again. This time he made an LP containing ragas Lalit and Megh and this was all that could be obtained from him before he was lost to the world.

It was my ardent desire to record as many eminent artists as was possible and to get out of each as much as I could to preserve their art for posterity. Bade Gulam Ali, Alla Diya Khan, Amir Khan, Kesarbai Kerkar, Rajaballi, Amanat Ali, all these and others of that generation had extremely old fashioned, conservative outlooks and were peculiarly obstinate when it came to recording their talents. This attitude prevented me from fully achieving my goal, and a wealth of art vanished along with these great singers.

I felt very distressed at Amir Khan’s sudden death. I still have feelings of great disappointment and frustration when I think of the number of opportunities I lost.

Born in April 1912 in Kalanaur, Amir Khan began his musical training as a Sarangi- disciple of his own father Ustad Shahmir Khan, a noted Sarangi player who had learnt his art from Chajju Khan and Nazir Khan of the Bhindibazar gharana. Amir Khan’s early grooming in Sarangi was only the foundation of his musical edifice. He had a vision and imagination of his own for higher artistic flights. Being a reputed artiste and a warm friendly person, Shahmir Khan’s hospitable home was a veritable rendezvous of many great contemporary maestros like Ustads Allabande Khan, Jafruddin, Nasiruddin Khan, Beenkar Wahid Khan, Rajab Ali Khan, Hafeez Khan, Sarangi- nawaz Bundu Khan, Beenkar Murad Khan and several others. Thus, although Amir Khans’s early musical training commenced with Sarangi, the impressionable and intelligent youngster was constantly exposed to the various vocal gharanas of the times. Gradually, Shahmir Khan himself began to devote more time to Amir Khan’s vocal training in which merukhand (or Khandmeru) practice and sargam-singing were specially emphasised. Moulded by the styles of three great giants of his younger days, namely, Ustads Bahre Wahid Khan, Rajab Ali Khan and Aman Ali Khan, Amir Khan evolved his own stylistic school which came to be known as “the Indore Gharana.”

In fact, Amir Khan was a self-taught musician. He assimilated the distinctive features of the gayakis that appealed to his aesthetic sense and were in perfect accord with his voice. The style that he evolved was a unique fusion of intellect and emotion, of technique and temperament, of talent and imagination. His style was a synthesis of three different styles. He assimilated the colour and spirit of Wahid Khan’s style, (with its chastity of swara intonation and a richly soporific effect of melodic elaboration) so well that Ustad Wahid Khan blessed him. “Long shall my music live in you after I am gone”. The slow Khayal is rendered in such a slow tempo that it has “the langour of unfinished sleep.” This style originated in the Merukhand style of the Bhindibazar-gharana. This generally strove to produce the permutations and combinations of a given set of notes. These are like mathematical exercises with little artistic effect in a concert. The development of the Vilambit Khayal was marked by deep serenity. The concept of an extra slow tempo with a slow and meticulous unfolding of the raga and the “cheez” was taken from Ustad Bahere Wahid Khan. His taans were clearly influenced by the eloquent ones of Ustad Rajab Ali Khan. In sargam-singing, he revealed his admiration for Ustad Aman Ali Khan. During his early sojourn in Bombay, Amir Khan had be come a close friend of Late Aman Ali Khan. Amir Khan always maintained that had Aman Ali Khan lived longer he would have been the former’s “confrere in the world of music”. This newly amalgamated “Indore” style of Ustad Amir Khan captivated and influenced a whole generation of younger musicians of all categories through the contemplative and reposeful beauty of his slow, leisurely Badhat (elaboration) enlivened by the “exuberance of his proliferating sargams” and rushing taans. So tremendous has been the impact of his distinctive “gayaki” on the rising generation of young Hindustani vocalists that Amir Khan commanded a large following among the younger aspirants. He no longer remained as an isolated individual.

For years, he remained one of the most sought after classical vocalists of his times. What set him apart from his contemporary artistes was the fact that he never made any concessions to popular tastes, but always stuck to his pure, almost puritanical, highbrow style. “His music combined the massive dignity of Dhruvpad with the ornate vividness of Khayal”. There are some musicians of the Kirana school who argue that the words of the Khayals are of no importance ! But Amir Khan held different views. He used to say: “The poetic element in Khayal is as vital as its melodic element. An artiste has to have a poet’s imagination to be a good musician”. Amir Khan has proved that “chaste refined music does not lack listener-response”, for, he strictly remained uncontaminated by the present craze for showiness. The tall, handsome Ustad had a dignified concert presence. His dignity of bearing and his posture of Yogic calm on the stage struck a perfect accord with the serene grandeur of his music. It was as though his musical thought was in tune with some ideal of beauty and he was striving to communicate it to his charmed audience”. As Prof Sushil Kumar Saxena wrote (in the Sangeet Natak Akademy Journal 31) “An Amir Khan swara was at once a tuning of the self, a calm that spreads while Ghulam Ali’s glows with a pulpy luminosity.”

Amir Khan’s forte was the exaggeratedly slow or ati vilambit Khayal which he developed in a most leisurely mood with deep serenity and contemplativeness. While his ardent admirers found this part of his concert absolutely engrossing, there were others who found it “excruciatingly slow” or even “insipid”! He always avoided Sarangi accompaniment, and wanted nothing more than a steady, plain Theka from his Tabla accompanist. His favourite slow talas were Jhoomra and Tilwada. Words were subservient to the “absolute music” that he sang, and naturally, “bol-alaps” and “Bol taans” were conspicuously absent in his singing. In the course of his prolonged unfoldment of the vilambit Khayal asthayi, Amir Khan would sometimes render flashing “meteoric taans”. His “taans” were marked by many graces like elegant gamaks, lahak and clear “daanas” (clarity of each note). It was natural that the Ustad always chose highly serious, expansive, traditional ragas like Todi, Bhairav, Lalit, Marwa, Puriya, Malkauns, Kedara, Darbari, Multani, Poorvi, Abhogi, Chandrakauns and so on. Even the lighter ragas like Hamsadhwani acquired a serious expansive mood when rendered by Amir Khan. His rich, mellow voice was at its best in the deep, dignified “mandra” notes (lower notes). His voice had some inherent limitations, but he shrewdly evolved a style to suit his voice.

Summing up the essence of his father’s vocal style, Ekram Ahmad Khan (the eldest son of the Ustad) wrote: “Amongst the elder maestros of music, Khan Saheb was intensely devoted to Rajab Ali Khan of Dewas, and Aman Ali Khan of Bhindibazar. He also studied the styles of Bahere Wahid Khan and Abdul Karim Khan and amalgamated the essence of the styles of these four maestros with his own intellectual approach to music, and conceived what is now known as the Indore gharana of music”.

During the first 25 years of his life, Amir Khan devoted considerable time to sargam- singing, what is known as “Merukhand practice” consisting of varied permutations and combinations of kaleidoscopic swara-patterns. These complicated “Khandameru” sargams, and flashing meteoric taans brightened his reposeful vilambit Khayals now and then. The ”Merukhand” style of singing is mentioned in the l4th century Sanskrit classic Sangeeta-ratnakara of Sarangdeva.

Another significant aspect of Amir Khan’s art imparting it a unique quality, was his refined voice and the way he moulded it to suit his chosen style. Endowed with the face of an intellectual, his temperament, like his music, was serene, unruffled. He never lost his temper. He extended the same courtesy to all, big and small, and listened attentively to even lesser artistes. Humility was native to him, his judgements were generous, and he was above petty jealousies.

Although Amir Khan never rendered Thumris in his concerts, his disciples speak of the exquisite way in which he rendered Thumris for them in his intimate home-circle. His “cultured” voice was suited for the melodious Thumri style also. Amir Khan’s sole concession to the speed-loving contemporary listeners was the Tarana in which he did considerable research. According to him, the Tarana-syllables have a mystical significance. Although his voice was at its best in the lower notes, it could also soar and sweep across far-off swaras with nimble grace. Such was the influence of his music that in an era of impatient listeners, Ustad Amir Khan was able to instil, by the example of his own art, a genuine and widespread love for serious, contemplative music into the hearts of young music lovers all over the country. He was strongly against the idea of any short-cuts to success in music.

Even when Amir Khan did playback singing for some films, he refused to cut adrift from his classical moorings. The songs he rendered were always in highly classical style and in ragas like Darbari, Adana, Megh, Desi, Puriya Dhanasri etc. In his tribute to the Ustad, Prof S.K. Saxena writes in the Sangeet Natak Akademi Journal: “Amir Khan was different and solitary because of his absolute indifference to the reactions of his audience while he was singing. He never seemed to make a conscious endeavour to please the audience. He faced them majestically, with his music alone, and with pure classicality. Often his music seemed strangely disembodied from raga-tala distinctions into a kind of musical incense borne aloft on the very wings of devotion. His music, at its best, was rarely a dazzle. It would be rather an influence, an atmosphere which would just be with us till long after the recital”.

There was a time when Amir Khan was a rage in Calcutta and no music conference there was complete without his recital. The Films Division of the Government of India has brought out a documentary film on his life in recognition of his great contribution to Hindustani music. For his eminence as a performing artiste and for his significant contributions to classical music, he was crowned with many honours such as the Fellowship of the Sangeet Natak Akademi, the Presidential Award, Padma Bhushan (1971) and the Swar Vilas from Sur Singar Samsad (1971). But these honours and his large following in the music world left him untouched. Amir Khan continued to be a very simple individual “accessible to all and sundry”, and he never assumed any airs like some of his contemporaries. Though not educated in the formal sense, he was a highly sophisticated person who moved with dignity in the highest society where he was genuinely revered. It was considered a privilege to be his friend. Through his own efforts, he learnt Hindi, Urdu, Persian and a bit of Sanskrit, and he studied the writings of Guru Nanak, Vivekananda, Ramakrishna Paramahamsa and others. Khan Saheb’s son Ekram Ahmad Khan writes that it was these studies and his close friendship with Narayan Swami (of Calcutta) that led to his unique blend of Sufism. “Khan Saheb”, writes his son, “was a Sufi in the true sense of the word - a man without any specific religious ties, a man totally devoted to the oneness of mankind, a true citizen of the World”. Amir Khan was a good composer and some of his compositions reflect these religious convictions of his. One instance is “Laaj rakh lijyo mori, Saheb, Sattar, Nirankar, Jai ke Daata, Tu Raheem Ram Teri maaya aparampar, Mohe tore karam pe aadhar Jag ke daata.” Whenever I heard Amir Khan singing the Khayal in Bairagi beginning with the words “Man sumirat nis din tumharo naam”, I felt that the words and the spirit of the raga were most aptly suited for Amir Khan’s musical temperament.

Since 1968, Khan Saheb used to go to U.S.A in alternate years to spend the summer with his son Ekram Ahmad Khan, a graduate in chemical engineering from McGill University who has settled down in U.S.A as an Engineering Manager in Canada. [Sounds odd, doesn’t it? Maybe he lives in Buffalo and drives to Toronto for work:-). I wonder where Ekram is today and if he has any private unissued recordings of the Khansaheb – RP] Amir Khan also used to go as a visiting professor of music at the State University of New York at New Paltz where “he planted not only the seeds of his music among the students, but also left behind the legacy of his Sufi philosophy”.

Unassuming in his ways, Amir Khan had the capacity to adjust himself perfectly to his environments. He seemed equally at home among the humble as well as among the highly sophisticated. What a pity that this great artiste was snatched away in the peak of his career! Here was a rare classicist who sustained his art by pure devotion, and yet enjoyed wide popularity. Even now, more than 7 years after his untimely death, Amir Khan’s music is still a living force because his voice is being frequently heard over AIR through his recordings in the Archives and his Long Playing Records. The Indore gharana of Amir Khan continues to live on through his pupils like Amarnath, Kanan, Srikant Bakre, Singh Brothers, Kankana Banerji, Poorabi Mukherji and others. There are many others whose singing has been obviously coloured by the style of Amir Khan. The singer is gone, but his music is still with us.

*****

USTAD AMIR KHAN by G.N. Joshi

The death of Ustad Amir Khan in a tragic motor accident in Calcutta a few years ago has created a void in the world of Hindustani classical music. At the present time, when there is a dearth of such gifted artists, his death is an irreparable loss. Had he lived longer he would have had, at least, a number of able and talented disciples to carry on the tradition of his gharana.

In the last 25 years some artists have, by their revolutionary spirit, progressive outlook and creative faculties brought about radical changes in the style of presentation of classical music. Ustad Amir Khan was such an artist. Like Kumar Gandharva. Amir Khan disregarded the age-old, conventional traditions, and with his intelligence and talent evolved an entirely original style of presentation. He also succeeded in gaining the approval and recognition of critics and connoisseurs.

Amir Khan was born at Indore in 1912. Music was in his blood; his ancestors had been musicians in the Mughal courts. His father was an expert sarangi and veena player. A mehfil of Amir Khan’s was always a pleasant experience. He had a very impressive and magnetic personality. At his concerts he would always sit in the posture of a yogi doing his tapasya, with closed eyes and deep meditation. He maintained the same position till the end of his concert. His smiling countenance, a total lack of gesticulation or facial distortion, his absolute concentration on the song, and the slow, gradual build-up of a raga picture invariably kept his audience completely engrossed. He had, for accompaniment, two tanpuras tuned to perfection, a subdued harmonium and a tabla with a straight, simple but steady laya. An atmosphere of solemnity and tranquillity pervaded his concerts, in striking contrast with the noisy and sometimes unmusical gymnastic bouts some singers have with the tabla players that entertain listeners with acrobatics rather than providing them with aesthetic delight.

He had cultivated his voice till it was as exquisitely chiselled as a piece of sculpture. While presenting a raga he unfolded it with extreme skill, delicacy and purity. At times, when an ascending note appeared to be suspended in mid-air, he unexpectedly made a lightning play on that note, holding the audience spellbound. Because of his inborn, instinctive knowledge of avakash, kal and laya he was able to make his voice sound as if he was singing swaras from two different octaves simultaneously, treating his audience to a unique celestial experience. His mastery over layakari and the swaras was complete. His taans though complicated, and full of artistic twists, were executed in an easy and graceful way. He had an amazingly wide range of pitch, and he moved majestically through this span with his liquid golden voice. Listeners were always favourably impressed by his gayaki and skilled display of tonal beauty. He did not agree with the popular notion that the tarana was just a tongue-twisting exercise with a meaningless cluster of words, involving a lot of vocal jugglery in an ever-increasing tempo. He always put into a tarana a Persian couplet interwoven in the apparently meaningless ‘Dir tun, tan, din yalali, yalallum’, and honestly believed that these syllables did have some mysterious and mystic import. According to him it was the Persian scholar Amir Khusro who invented the tarana. Amir Khan was very keen on establishing this theory by carrying out research to unravel the hidden meanings of the tarana. But cruel destiny snatched him away and his mission was left unaccomplished.

Amir Khan’s presentation was always thoughtful and methodical and he rarely indulged in repetitive phrases. The thorough treatment he gave each raga naturally required considerable time for flawless elaboration. It was well-nigh impossible to get a satisfactory exposition from him in just 3 minutes. It was therefore only in the late 1960s that I could have him to record for a long-playing disc (in effect, it must have been in the late 1950s and the recordings in question are the ones we post here on his very first LP). It was not an easy job to bring him before the mike, though obtaining his consent was not all that difficult. Even to approach him posed a very big problem for me. Amir Khan lived, in those days, in very disreputable surroundings, where it was considered very objectionable for any gentleman to go, even during the day. This is the locality a little beyond and opposite the Congress House on Vallabhhhai Patel Road, near the Kennedy bridge. It is inhabited by professional singing and dancing girls, as well as prostitutes. Amir Khan was giving tuitions to some of these singing girls for his living and therefore had to stay in one of the buildings on the third floor. Later, when his financial position improved, he shifted to a flat on Peddar Road. Just beyond the building where Amir Khan lived was the residence of an elderly singer by the name of Gangabai. Ustad Bade Gulam Ali Khan and Ahmad Jan Tirakhwa often stayed with her. This shows that even women of these professions were treated with respect as artists, in artistic cirles. As the recording executive of H.M.V. I had to contact artists regardless of time and place.

To obtain Amir Khan’s agreement for the recording I had to meet him, and, therefore it was incumbent on me to visit his residence. I was greatly put off when I learnt about the locality where he stayed. I was afraid of what people would say if they observed me entering a house of ill repute. Any outsider would naturally draw his own conclusions, not knowing that an eminent singer was living in that building. If I had, out of fear of social stigma, refrained from going to visit Amir Khan, his great artistry would have gone unrecorded. The idea of securing his consent for recording together with a keen sense of duty prompted me to enter the building, eyes downcast, not looking about me till I entered Amir Khan’s room on the 3rd floor. Once in his room I cheered up, and I talked to him for an hour or two. After that I visited him often. We exchanged views on music and gharanas, and such visits gave me opportunities to study his likes and dislikes. These visits also gave him confidence in me. After a couple of months and 4 or 5 such visits, he agreed to come for a recording. Some more time was lost in persuading him to agree to the terms of payment. Finally this hurdle too was crossed. Yet Amir Khan went on cancelling dates, giving fresh ones and then again postponing the recording on some flimsy ground. I got fed up with his dilly-dallying and, in spite of my great regard and respect for him, I justifiably felt very annoyed. Ultimately one day I plucked up my courage and said to him, ‘If I had approached God Almighty as many times as I have come to you, he would have blessed me, but all I can get from you is the promise of a future date.’

Seeing my exasperation he became thoughtful, smiled a little and replied, ‘Please do not disbelieve me. Name any day of this week and I will keep the appointment.’ True to his word he came on the day I named, and I got from him his first long-playing disc. His favourite ragas were Marwa, Darbari Kanada and Malkauns. It is indeed rare these days to hear Raga Marwa as it was presented by Bade Gulam Ali and Amir Khan. His first LP was received with tremendous enthusiasm by the public. This delighted Amir Khan, and he was more than ready for another recording. In spite of this I had to put in a lot of effort and time to bring him to the studio again. This time he made an LP containing ragas Lalit and Megh and this was all that could be obtained from him before he was lost to the world.

It was my ardent desire to record as many eminent artists as was possible and to get out of each as much as I could to preserve their art for posterity. Bade Gulam Ali, Alla Diya Khan, Amir Khan, Kesarbai Kerkar, Rajaballi, Amanat Ali, all these and others of that generation had extremely old fashioned, conservative outlooks and were peculiarly obstinate when it came to recording their talents. This attitude prevented me from fully achieving my goal, and a wealth of art vanished along with these great singers.

I felt very distressed at Amir Khan’s sudden death. I still have feelings of great disappointment and frustration when I think of the number of opportunities I lost.

Both articles are taken from: https://www.parrikar.org/vpl/?page_id=353

3 comments:

Thank-you very much

Sir please upload badi moti nai rasoolan bai and siddheshwari devi recordings

Its a great post. Please upload more and more of the legends recordings like Ustad amir khan, Pt. Bhimsen Joshi. Great job

Post a Comment