Oriental Traditional Music from LPs & Cassettes

Thursday, 28 March 2019

Friday, 22 March 2019

Azam Bai (1906-1986) - An All India Radio Release - Cassette released in India in 1990

We discovered two more cassettes by great female singers of the Jaipur-Atrauli Gharana in our collection. Here the first one with AIR recordings by Azam Bai. Among the maestros who guided her were Pandit Govindbua Shaligram, a disciple of the great Ustad Alladiya Khan of Jaipur-Atrauli Gharana; Pandit Vishwanathbuva Jadhav, a leading disciple Ustad Adul Karim Khan of Kirana Gharana and Pandit Nivruttibuva Sarnaik (see our last post), also a disciple of Ustad Alladiya Khan Saheb.

Monday, 18 March 2019

Nivruttibua Sarnaik (1912-1994) - Cassette released in India in 1993 - AIR recordings from 1977

Here we present some AIR recordings, released as a cassette and also as an LP in 1993 by the great singer Nivruttibua Sarnaik, a direct disciple of Ustad Alladiya Khan. His style is a little eclectic as he studied also, amongst others, under Sawai Gandharva and Rajab Ali Khan. He formed many students, amongst them many became famous musicians.

This is - as far as I know - the only commercial cassette and LP by the artist. In 2015 Meera Music published four CDs, which can be bought in India from Sonic Octaves or downloaded from CD Baby in the US.

All India Radio (AIR) recorded him a lot and many of these recordings one can find now on YouTube.

With this post we close our series of older masters of the Jaipur-Atrauli Gharana for now.

On the artist see:

Tuesday, 12 March 2019

Mallikarjun Mansur - Echoes of a Soulful Voice - Box of 4 cassettes released in India in 1992

The Lone Titan: Mallikarjun Mansur

MOHAN NADKARNI, the noted critic, pays a tribute to the maestro.

Music to Pandit Mansur is not just an avocation. With him, it is a way of life and through it, he seeks to express the very essence of his inward being. As he often declaims : “I have never let my thought and action deviate from my music.” Indeed he ‘lives’ it.

Incredible is about the only word to describe Pandit Mallikarjun Mansur, who turns 75 on December 31. He is the last titan still amazingly active on the Hindustani concert stage. And continues to sing with a verve, grace and vigour surprising for his age. Of course, his concert appearances are getting fewer – and naturally so, but whenever he condescends to sing in public, his music elevates him to a plane far, far above the vast multitude of his confreres, many of them eminent in their own right but much younger.

Mark, for example, the laser-beam precision of his swara; the crushing trenchancy of his taal; or the tremendous force and animation he imparts to his creative process; or the sculpturesque dignity, poise and balance that distinguish his melodies. These are all still here. Especially to his old-time listeners (like this writer), who have savoured his music for four decades, each of his latter-day mehfils comes as a stark reminder of a great era that is fast coming to an end.

His is, indeed, the voice of tradition – a tradition which looks almost doomed to be at the mercy of the man in the street sooner than later. Not for nothing has a multinational recording company managed to coax the maestro to cut a series of long play discs barely a few weeks ago!

My acquaintance with Mansur’s music was through his commercial records. That was in the early ’40s, when I was a college student. I still cherish the nostalgic memories of those three-minute discs of Goud-Malhar, Adana, Todi and Yamani Bilaval for their racing, sprightly musical lines, intricate rhythms and complex, odd-shaped taans. They had a stately quality which his tenor yet vibrant voice conveyed with a naturalness all its own. So abiding was their impact on my ears that I seldom missed an opportunity to listen to his radio recitals. (Public concerts were not so much in vogue then as they are today.)

Mansur’s recital at a Ganapati festival in Bombay, in 1945, brought me the long-awaited opportunity to listen to his ‘live’ music. It was a four-hour recital, comprising a rich and varied repertoire of popular as well as rare ragas. To my surprise and admiration. I also heard him render a couple of Marathi songs and Kannada devotionals in between.

The maestro was so sure of his touch that he totally dispensed with the preliminary alapi in the presentation of his individual ragas. Yet he established immediate rapport with his listeners by the very opening swara of his chosen raga. In no time did he work himself into an +intense mood and impart to his music the hue and character of his classical thought, his passionate urge for self-expression and instinctive feeling for the artistic. It was as though his musical thought was in tune with some high ideal of beauty and he was striving to communicate to us with the fire and fervour of an impassioned utterance. Few, indeed, are great musicians like Mansur – who unfailingly share their pure, sensuous joy with their listeners from start to finish. And that is what makes a Mansur concert an event always to look forward to even today.

Mansur’s gayaki, to my mind, is a rare assimilation of three musical streams – the tradition of Carnatic music and the two vocal traditions of Gwalior and Atrauli-Jaipur. He had his initiation into the Carnati paddhati from Appayya Swami, a veteran vocalist, violinist and playwright of his time. He was then placed under the tutelage of Nilkanthbuva Alurmath, a leading disciple of the maestro Balkrishnabuva Ichalkaranjikar, who is credited to have brought the khayal style of singing from Gwalior to Maharashtra.

After six years’ grooming in the Gwalior parampara came the final and most decisive period of shagirdi in the Atrauli-Jaipur gharana of which Alladiya Khan is considered as the pioneer. But it was not this ustad, but his two worthy sons, Manji Khan and Bhurji Khan, who moulded the musical genius of Mansur. Manji Khan’s sudden and untimely death, within barely two years, left young Mansur without a comparable guru, while it also deprived the country of a musical luminary who, by all accounts, would have been excelled hi father. But it was not long before Bhurji Khan took his departed brother’s protégé under his wing and shared his vidya with him for several years.

It is often said, not without a degree of justification, that the Atrauli-Jaipur gharana, with its dhrupad-like massive form and robust structure, does not lend itself to free and unfettered Interpretation and, for that reason, does not command much popular appeal. It is also argued that it is the felicitous emphasis on layakari and the penchant for ingenious phirat that greatly help to hold the audience’s attention. In other words, the impact of the music is intellectual, which affords little scope for the exponent to show his individual musicianship.

Manji Khan was, by common consent, something of a rebel, determined to widen the horizons of his gharana without compromising, in the least, on its fundamentals. He lent it a refreshing quality of romanticism – as Abdul Karim Khan did to his Kirana gharana and Faiyaz Khan to his Agra gharana. And thereby he evolved a style which was marked not only by the purity and vigour of Alladiya Khan but also the subtlety of his own imagination. Although he did not live long to watch the success of his new genre, it was left to Mansur to promote and popularize it. Here indeed, lies the distinctive character of Mansur’s contribution to the Atrauli-Jaipur gharana in particular and Hindustani music in general.

Another important aspect of Manji Khan’s approach to music deserves mention. It is his progressive outlook, conditioned by an awareness of the tastes and preferences of his audiences. This was reflected in his repertoire, which included a judicious mixture of light and popular songs, like Marathi bhavgeets, natyageets and bhaktigeets. This has also been the format of Mansur’s concert fare for several years. It is only in recent years that he has restricted his singing to khayals. Only in very rare cases, and that too, in response to pressing request, does he end his recitals with a Kannada devotional or two.

Mansur gratefully says that Manji Khan’s vocalism has had the most abiding impact on his style. This is also the opinion of those who were au fait with his mentor’s style. They are, in fact, all admiration for the way Mansur – incidentally, the ustad’s only worthy shishya – has imbibed even the spirit of his guru’s approach. All this, within an incredibly brief period of studentship!

Mansur is equally grateful to his other gurus who contributed significantly to the moulding of his musicianship. He says his first teacher saw in him the makings of a future musician and initiated him into the mysteries of Carnatic tone and rhythm. Alurmath groomed him in the tradition of the Gwalior gharana, with special emphasis on aakar, alamkar, swara, taal, laya and brief compositions in popular ragas. The grooming from Bhurji Khan, which was the longest, gave him a thorough insight into the laya-oriented, dhrupad-based style of Alladiya Khan along with a rich repertoire of rare and complex ragas.

And Mansur, in my opinion, is the only maestro who can present such an amazing variety of less-known ragas as naturally, as spontaneously, as the familiar ragas. Incredible though it may seem, the number of melodies I have heard from him comes to 125! If his depiction of familiar melodies unfolds their unsuspected niceties and beauties, he reveals his savoir faire in making an uncommon raga sound easy and simple and project it as a well-knit, aesthetic build-up.

Strange but true, Mansur chose to remain away from the limelight till he reached 60. At least his concert visits to Bombay had become rare. Meanwhile, I also gathered that he had accepted – after persuasion – a 10-year assignment as music adviser with AIR, with headquarters at Dharwad, in Karnataka. In keeping with his nature his involvement with the job was so total and complete that he seldom stirred out of Dharwad. Evidently, during this period, he spurned offers for concert recitals, so much so that music circles in Bombay lost sight of him till 1969.

The late Kamal Singh, the popular thumri and ghazal singer, who had started his Sangeet Mehfil to organise periodical sangeet sammelans in the city, asked me to suggest names of top artistes who had not performed on the concert stage for a long time. He was planning his annual soiree early that year. He was visibly baffled at my suggestion of Mansur’s name for his sammelan. Sensing his predicament, I assured Kamal Singh that Mansur was quite hale and hearty and musically active, too, leading a quiet life in his home town after retirement from AIR.

And it was Mansur’s recital for the Sangeet Mehfil in March 1969, that truly marked his return to an active concert career – and that, too, with a bang! He has never looked back since then. Needless to say, his visits to Bombay became very frequent and, in time to come, he became an all-India figure.

Titles, awards and honours began coming to Mansur in profusion: Padmashri in 1970; President’s Award for Hindustani vocal music and Padma Bhushan, in 1976; honorary D Litt from Karnataka University, in 1975; and Kalidas Samman, the prestigious Rs. 1 – lakh award instituted by the government of Madhya Pradesh, in 1981. More recently, he has been nominated as a member of the Karnataka State Legislative Council. He is currently dean of the faculty of music of Karnataka University and, in that capacity, he guides its destiny with typical devotion even while performing at major musical events all over the country.

I have been one of his Bombay hosts during his concert visits to this city over the last 15 years. And with Mansur at home, it is music, music all the way. It is during his brief sojourns that I could get many glimpses of his personality as an artiste as well as a human being. Profoundly simple and humble, there is nothing vain, eccentric or capricious about him. He has both genius and spirit but does not display them. I have often found it ticklish to draw him into a conversation though he delights in informal chats.

During one such conversation, not long ago, the maestro burst into a thumri, a tappa and a dhamar – the forms he has never presented at public concerts. These revealed new facets of his versatility and came to me as a revelation. In reply to my question, he simply said that he was basically a khayalist and always remained true to the spirit of the Atrauli-Jaipur gharana. He asserted that the khayal style embodied all that is best in the Hindustani tradition of classical and light classical music, which is why it continues to be the most popular style of classical singing.

Panditji’s has been high pitched singing. When I sensed a slight degree of tiredness creeping into his intonation, especially in the post-interval part of his concerts, I made bold to ask him, with utmost caution, if he could not bring down his aadhaara shadja (tonic or base note) to a lower key. To my relief and joy, he instinctively understood the import of my suggestion and acted on it, adopting what is popularly known as the ‘Black Two’ key of the harmonium, for his tonic. This was about a decade ago.

Although, even at 75, he has plenty of muscle in his voice, both emotional and physical, his listeners cannot but notice that it is no longer plentiful enough to sustain him uniformly in a full-fledged concert lasting three hours or so. That is because he loses himself in his creative ecstasy and oblivious of his advancing years, strains himself needlessly when he switches over to the faster movements in singing. The result is that more often than not, the maestro clearly looks frayed during his post-interval singing. When, recently I sought to plead with him, through my review column in The Times of India, to counsel a degree of moderation in expending his physical energy, his reaction was not one of annoyance, but of helplessness. “I simply can’t manage it,” he said, with a disarming laugh.

Music to Pandit Mansur is not just an a vocation. With him, it is a way of life and, through it, he seeks to express the very essence of his inward being. As he often declaims: “I have never let my thought and action deviate from my music.” Indeed, he ‘lives it’. Those who have chanced to visit him at his Dharwad residence in the morning hours will know what I mean. You will hear him sing when he is plucking flowers in his garden for his pooja. There is an incantational fervour in his musical soliloquy. The soulful strains elevate you even as they mingle with the wafting breeze. The same spirit pervades his pooja room when, after his bath, Panditji sits to offer prayers to his deity, Lord Shiva, with flowers and music, which is often an invocatory bandish, like ‘He Mahadev’, in Bahaduri Todi, or ‘He Narahara Narayana’, in Bibhas, taught to him by his musical mentors.

A deeply, religious man, Panditji attributes his attainments equally to his professional mentors and spiritual gurus. He refers feelingly to the blessings bestowed on him by three eminent saints of Karnataka – Siva Basava Swami, Siddharudha Swami and Mrityunjaya Swami. He began his concert career as a boy of 15 with his recital before Siva-Basava Swami and he has named his house after Mrityunjaya Swami. He firmly believes that his association with these saints brought about radical change in his temperament.

Panditji planned to retire completely from his concert career shortly after his 75th birthday and devote the rest of his years to matters of the spirit – and understandably so.

“The Tradition of Hindustani Music may die”

The reclusive Mallikarjun Mansur rarely talks to the press. Here, Mohan Nadkarni reproduces excerpts from discussions he had with the maestro on earlier occasions.

Pandit Mallikarjun Mansur is a man more inclined to listen than to speak. It is only rarely that he condescends to talk about himself and that, too, when his mood permits. Lately, the maestro has developed a strong dislike for formal, long-drawn-out interviews if it is meant for publication. So much so that when I sought an interview with him during his visit to Bombay last month, pat came his reply: “You have known me so well for so long. No more interviews to you or to any one else. I am tired of talking about me or my music or my professional career.”

Over the years, there have been innumerable occasions for animated conversation and discussion with him on the contemporary classical music scene. I have had the good sense to record the impressions of important discussions with him in the past. Here are some excerpts:

On family background and early career:

I owe my surname to my native village in Dharwad district in Karnataka state. I was married at the age of 10 to a girl of 5. There was no music in the family, but my father was deeply interested in musical drama. I was first attracted to the stage while only eight. I left school and joined a Kannada drama troupe of which my elder brother, Basavaraj, who later became a noted stage-actor, was a partner. I became very popular as an actor-singer when I was still in my teens. I played a variety of roles in many Kannada mythologicals which were the rage of those days.

On his switchover from musical drama to Hindustani classical music:

As is now known, I had learnt the basics of Carnatic music from Appayya Swami, who himself was an employee of the drama company in which I worked. Later, I joined another touring troupe and during its sojourn at Bagalkot, in Bijapur district, I chanced to hear a recital of Nilkanthbuva Alurmath. He was a veteran exponent of the Gwalior gharana of Hindustani music and I was greatly fascinated by his performance. He also heard me on the stage and, in response to my request, he readily took me as his disciple. My company even agreed to pay him a monthly remuneration of Rs. 100 to teach me!

On how and why he sought further grooming in the Atrauli-Jaipur gharana:

During my company’s camp at Miraj, I had an opportunity to hear the great stalwart, Alladiya Khan, who was the founder of the Atrauli-Jaipur gharana. The impact of his music made such a deep impression on my mind that I began cherishing the ambition of learning from the ustad. His age and eminence forbade me from approaching him. My mind was distraught and I came to Bombay in search of a comparable guru after leaving my studentship with Alurmathbuva and also the dramatic company. Rambling through the city streets. I happened to meet Vishnupant Pagnis, the famous Marathi stage and film actor-singer and also a leading jeweller. I learnt that he was a close friend of Ustad Manji Khan, the young, versatile exponent of the Atrauli-Jaipur gharana and son and disciple of Alladiya Khan Saheb. Fortunately, Pagnis had heard my first gramophone disc which was already out. To introduce me to Manji Khan, he played my disc before him. Deeply impressed by my singing, he gladly accepted me as his disciple. But Manji Khan Saheb died suddenly and prematurely in less than two years and I was left without a guru. A little later, Bhurji Khan Saheb, the late ustad’s younger brother, began teaching me systematically. He also took me along with him on all his professional tours. This gave me valued concert experience.

On the future of Hindustani music:

The great tradition of Hindustani music may die, unless proper steps are taken to impart its training systematically. Of course, there is no dearth of talent. But there are no facilities to make them perfect artistes.

On music education in universities:

What is being taught in the music schools, colleges and universities helps the students only to the extent of understanding the basic principles of music. It is sad that music students are required to have formal educational qualifications. This naturally prevents talented young artistes, deprived of formal education, from joining the music courses in the universities. You will be interested to know that I have made a departure at the Institute of Fine Arts of Karnataka University in this respect. I have thrown open its six-year certificate course in music to all those who are genuinely interested in learning music. This is irrespective of their educational qualifications.

On guru-shishya parampara:

I am a gharana man. The gharana system is vital to our tradition. Without it we can never have a generation of true artistes. Can there be a real kalakar emerging out of the present-day educational system? On his shishya parampara: There is a general lack of competent gurus in the field. This lack is matched by absence of dedication and discipline among students. Speaking for myself, I have tried to teach many students but few of them have ever cared to pursue their profession seriously. On audience appreciation of Hindustani music: Not all those who hear classical music today can be said to have real love or taste for it. Times have changed and we have come to live in an age of mass appreciation. The masses should be helped to understand and appreciate the finer points of classical music in several ways, for example, by explaining to them, in simple language, what is swara, laya, bandish and the like.

On the influence of film music:

Film music has had no influence on classical music. If anything, it is rather the other way round. See how film songs based on classical music enjoy continued popularity! Sadly, film-makers and music-makers have wrong ideas about popular tastes and provide them with hybrid, unwholesome music.

On experiments and innovations in music:

Do you mean the whole crop of new ragas? These are nothing but pruned, twisted versions of our time-honoured melodies. A whole life-time will not suffice to explore the vast variety of siddha ragas. There are hundred of old and also unfamiliar ragas waiting for the right artiste to unfold them.

On unification of Hindustani and Carnatic music:

Unification of he two paddhatis may be possible in the distant future, but certainly not feasible. The two systems have grown and prospered in peaceful co-existence for centuries. Why then force them to come closer? In that event, both will lose their distinctive individually.

On Western interest in Indian music:

I haven’t cared to go on a concert tour abroad. But I welcome this ‘export’ of music. It is a laudable effort, in so far as music-loving Indians residing abroad are concerned. Being far from their motherland, they feel starve of our music. As for foreigners, they seem to attend Indian music concerts largely out of curiosity and partly to please their Indian friends. Ironically, our artistes except in a few cases, seem to indulge in musical gymnastics and gimmickry in an attempt to dazzle the audiences there. On their return home, they demonstrate before their home audiences what they did abroad and how they won their applause. This trend has caught on in the country – mostly among instrumentalists – and their audiences. If it goes unchecked, it is going to be suicidal.

On music criticism:

I believe that the performing artiste should be able to assess for himself the standard of his performance. Personally, I do not even care to look at press reviews of my concerts. Barring a few rare cases, there is no informed and unbiased comment from reviewers. For a proper understanding and appreciation of classical music, critics as well as audiences, should be knowledgeable tolerant and also impartial.

from: http://www.mohannadkarni.org/the-lone-titan-mallikarjun-mansur/

Sunday, 3 March 2019

Mallikarjun Mansur - Morning and Evening Ragas - LP released in India in 1979

This is the companion LP to the one released a year earlier by the same label and which we posted in 2017: Pandit Mallikarjun Mansur sings rare and complex Ragas, our favourite Mallikarjun Mansur LP and the one with which we discovered this completely oustanding artist, one of our most beautiful musical discoveries ever. Both LPs were probably recorded in the same recording session.

This LP was republished several times as a CD, but the LP sounds so much better. I was only quite recently able to acquire it as an LP.

This is already our 10th post by this artist and will not be the last, insha'Allah. See here for the nine previous ones:

Monday, 25 February 2019

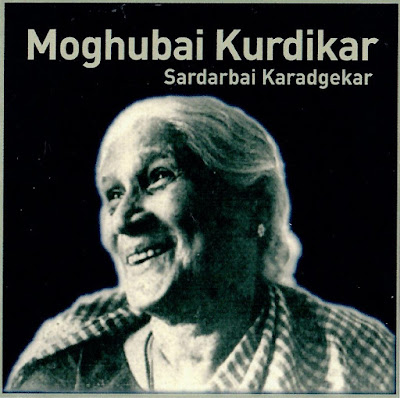

Raga Basanti Kedar - Mogubai Kurdikar & Sardarbai Karadgekar

Here we present a private CD with two versions of Raga Basanti Kedar: one by Mogubai Kurdikar and one by Sardarbai Karadgekar, both of the Jaipur-Atrauli Gharana from around the same period. Whereas Mogubai Kurdikar was very famous in her time, of Sardarbai Karadgekar one hardly knows anything. Apparently she was a disciple of Nathhan Khan (Alladiya Khansaheb’s nephew). She is also said to have learned in her later life from Nivruttibua Sarnaik, like her from Kolhapur and one of the main disciples of Ustad Alladiya Khan. We will post recordings by him in the near future. In 2011 we had posted a double cassette with a Raga Bihagda by Sardarbai Karadgekar .

We received this CD from our friend DM in the early 2000s. Many thanks to him.

Friday, 22 February 2019

Mogubai Kurdikar (1904-2001) - Cassette released in India in 1988

Here a collection of 78 rpm records by the other queen of the Jaipur-Atrauli Gharana. Today she is mainly still remembered as the mother of Kishori Amonkar, the queen of the Jaipur-Atrauli Gharana of her generation.

http://www.mohannadkarni.org/the-last-titan-mogubai-kurdikar/

and the article below.

Our friend KF had years ago made a CD out of this cassette. Here the covers. The back gives the sources of the tracks.

by Gopalkrishna Bhobe (Translated from Marathi by Ajay Nerurkar)

The extremely difficult gayaki of the Atrauli Gharana has been studied by many in Maharashtra, but the honour of being the foremost vocalists in this tradition goes to Goans Surshri Kesarbai Kerkar and Gaantapasvini Mogubai Kurdikar. These humble devotees of music crowned the musical edifice erected by previous generations and lent an estimable character to Goan musical tradition.

The anguish Mogubai experienced in her pursuit of music made her unique. Balancing the cares of tomorrow on one hand and her tanpura in the other, Mogubai battled on a Yogic scale. She acquired the learning, but that wasn’t enough. She was ever unsatisfied - suffering from a sense of incompleteness. But it is this sense of incompleteness that also bestows a rare talent - a talent that constantly accompanies one like a shadow.

The previous generation of musicians had devotedly pursued music, studied it and become famous, but destiny was on their side. Inspite of an extraordinary intellect, however, luck was not in Mogubai’s favour. At the time, Goa’s Kalavant community was undergoing a revolution. The fame of musicians had spread everywhere. Every mother wanted her child to become a musician and bring honour to the family name. It was no surprise then that Mogubai’s mother Jayshreebai had the same ambition. With a seven year old Mogu in tow she walked the distance from Kurdi to Zambavli. She requested a Haridas who had settled here to teach her daughter music.

The buwa responded, “Bai, I wander from place to place and have no fixed abode. My stay here is of limited duration.” But Jayshreebai was insistent. “Teach her as long as you are here”, she said. He taught her as best he could during the remaining part of his stay. This interruption at the outset of her musical education was to haunt Mogubai all her life. Jayshreebai’s desire, however, did not dim till the end. She had vowed, as it were, to make her daughter a singer worthy of standing alongside the greats. Someone suggested she approach the songsters that toured with drama companies. Full of hope, Jayshreebai took Mogubai to a company called “Chandreshwar Bhootnath Sangeet Mandali”. They made this company their home. And this touring company took their destiny for a ride too.

This was a somewhat small drama company of that time. The bustle of their shows spanned twenty and sometimes all thirty days in a month. Jayshreebai had been sucked into a maelstrom. The owner of the company was shrewd. He gauged Jayshreebai’s needs, noted her daughter’s sweet voice and then lost no time in roping in Mogu for roles like that of ‘Prahlad’ or ‘Dhruv’. This premature burden on her daughter’s shoulders pierced the mother’s heart, but to hear her confident, melodious singing, her playful bantering with rhythm to applause was elysian. She would dream of seeing Mogu become a great singer in the future. She was not destined, however, to have this happen in her lifetime. Physical labour took its toll, she fell ill and then passed away leaving her only daughter, an orphan. While on her deathbed, she handed over the charge of her daughter to Balkrishna Parvatkar, a person from her own village who also worked for the company, and told him, “Please help my daughter become an eminent singer.”

On the point of death she had held Mogu’s hand in hers and said, ”Mogu, my soul will be around you at all times and only when you carve out a name for yourself as a great singer will it find salvation !” Mogu’s childish mind may not have made any sense of this, but the words themselves remained etched in her memory to the end. And when she understood what those words meant she vowed — ” I shall withstand boundless suffering, endure physical pain, even disregard humiliation to learn music and fulfil your desire !” Vows torment the sincere. They load the dice against them. Success comes in sight only when the verve has gone and only after a lot of sorrows have been digested. Such is the story of Mogubai’s life too. After Jayshreebai’s death, the drama troupe that supported Mogubai, ‘Chandreshwar Bhootnath’ was racked by internal fissures. Soon differences cropped up between the owners, and the company folded. Mogubai had to return to her village and somehow pass the time. Unexpectedly, one day, she received an invitation from another company, ‘Satarkar Streesangeet Mandali’. Balkrishna Parvatkar did not let this means of livelihood slip. He immediately had Mogubai join the company.

Gradually, the parts Mogubai played became popular and she got roles like that of Subhadraa in Saubhadra and Kinkini in Punyaprabhav. Her name was enough to sell tickets. All said and done, however, it was a drama troupe and one of women, to boot! Any drama company is born with the baggage of jealousy, rivalry and resentment. Things came to a head one day. Mogubai had to leave the company as a consequence of a severe quarrel with her mistress. One can only imagine what bitter disappointment and anguish Mogubai’s artistic soul must have felt as she made her way back to her village. What did the future hold for her except a return to the hard life of a drama company ? Had she fulfilled the promise she had made to her mother ? No ! Her life, however, was slipping away.

Mogubai’s studious mind had achieved two things while she was with the ‘Satarkar Stree Sangeet Mandali” — a compact training in Natyasangeet from the late Chintubuwa Gurav and primary lessons in dance from the company’s resident dancer Ramlal. Later, out of sheer interest, she had taken advanced training in dance from two proficient dance masters — Chunilal and Majelkhan. But this was just as a hobby. All this helped her imbibe the rhythmic aspects of music so thoroughly, that they now ran in her blood. Mogubai fell ill because of the heartache that leaving the drama company had caused her. A doctor recommended a change of climate. Acting on this advice, she set up residence in the nearby province of Sangli. There, on the suggestion of some well-wishers, she started learning from Khansaheb Inayatkhan. But, soon for some trivial reason, the whimsical Khansaheb stopped teaching her. This was the second setback her musical education had received in its infancy. Although her training had stopped, she continued to rehearse whatever little Khansaheb had taught her. She got so wrapped in this riyaaz that she forgot herself.

One evening she sat rehearsing an ornamental swara pattern she had learnt from Inayatkhan, completely absorbed in her own musical world, when her spell was broken by a noise that appeared to come from the doorway. She opened her eyes and there stood before her an elderly person with the looks of a yogi, a huge white moustache and wearing a pink turban. Her fingers lay still on the tanpura and her face took on a quizzical expression. Before she could speak, he said, taking a step forward, “Please continue your riyaaz. I listen to your singing everyday. Today, I came to see you in person.”

This was the first Mogubai had seen of Gaansamrat Alladiya Khansaheb.

Khansaheb was in Sangli getting treatment from the reputed doctor, Abasaheb Saambaare. His daily route took him by Mogubai’s house and each day he would quietly appreciate her mellifluous and cadenced voice. But today he couldn’t restrain himself. He saw who this voice belonged to, grasped her yearning for musical education and perhaps made up his mind about something, for there he was the next day, sitting before Mogubai and tutoring her in Raag Multani.

To Mogubai, his overall personality suggested only that he was probably a famous singer. Little did she know that he was a reigning monarch in the world of music. She comprehended just how great he was, when she attended a function at the residence of Abasaheb Saambaare. He was on the dais, ready to sing, and she observed how some very eminent people bowed to him in respect. She was astounded.

She swelled with pride. Scarcely could anyone be more fortunate, she thought. She was overcome with emotion, and her whole being trembled with happiness. However, the good fortune did not last long.

Her training with Khansaheb had completed 1 1/2 years. During this time she mastered raags Multani, Todi, Dhanashree and Poorvi. Khansaheb was delighted with his pupil’s intensely receptive nature. But it was a very restless Khansaheb that came to teach her one day.

He said, “I have to leave Sangli for Bombay. That will now be my permanent home. I am abandoning you, I have to.”

Tears flowed from Khansaheb’s eyes.

He continued, “If you come to Bombay, I will somehow find the time to teach you. You have understood my gayaki. Now it is only a matter of adding to your store of knowledge.” Khansaheb left for Bombay. Mogubai was distraught. Her training had been interrupted. What would she do now ? She was getting increasingly desperate. “What are you doing here ? Go to Bombay !”, she kept telling herself. But this was easier said than done. However, when one truly yearns for something one automatically acquires the strength to achieve it. During her stay in Sangli she had been inspired by the music of the late Rahimat Khan and of Pt. Balkrishnabuwa Ichalkaranjikar. Their lives were also intensely inspiring. Mogubai decided to take a leap into the unknown. She journeyed to Bombay where she found a small place for herself in Khetwadi. Also, she met Khansaheb and requested him to resume his tutelage.

Khansaheb was delighted. He started guiding her once more.

Now one would have expected things to go smoothly for a while. Alas ! Only a few days had passed when Khansaheb stopped coming for his regular lessons. Inquiries revealed that Khansaheb’s hosts in Bombay had forbidden him to train anyone else. They did not wish anybody else to carry the stamp of the Alladiya Khan gharana. Khansaheb was helpless. He had been fenced in by someone’s fear of being bested by a talented woman like Mogubai quickly absorbing his teaching. Unwittingly, Mogubai had created hidden enemies. Her training had been interrupted and it was as if the sky had fallen upon her. The very thing for which she had left all to come to Bombay was now nowhere in sight. Everything now seemed futile to her.

She spent several days worrying. Ultimately, in frustration, she requested Bashir Khan, a son of Bade Mohammad Khan, to train her. Bashir Khan agreed on the condition that she perform the ganda-bandhan with Vilayat Khan. Desperate to start learning again, she scraped together whatever little she had and put up a grand ganda-bandhan ceremony. Bashir Khan began to teach her. Naturally, Alladiya came to know of this. He feared that a different teacher would change the mould of her voice, something he had designed. He wanted someone as talented as Mogubai to continue in his musical lineage. One day, he went to Mogubai and said, “Mogu, stop your training with Bashir Khan. I will arrange for your tutoring with my brother Hyder Khan. The distinctive pattern I have given your singing should not be tampered with.”

Mogubai was speechless. Somehow she responded, “Khansaheb, you should be aware of what might ensue. First of all you are asking me to run afoul of somebody I’d rather not offend. You know the standing Bashir Khan, Vilayat Khan and their family enjoy in Bombay. I shall stop the training but only if you promise to take me as a student in the event of Hyder Khansaheb’s being unable to teach me anytime in the future.”

Khansaheb gave his assent and Mogubai began to receive systematic training from Hyder Khan. Mogubai’s acuity and Hyder Khan’s teaching abilities made a great combination. Every few days Hyder Khan would supply her with a new raag or a new cheez. Mogubai was busy taking in all he gave. In a short time Hyder Khan prepared her remarkably well. The future looked rosy to Mogubai, she dreamt of fulfilling the promise she had given her mother. But good fortune still refused to smile on her.

Mogubai’s fast-paced progress made Alladiya’s other pupils green with envy. The thought that Mogubai had shot ahead of them constantly pricked them. There was only one thing they could do. Persuade Khansaheb, warn him and get him to exert pressure. And that is what they did. Alladiya Khan compelled Hyder Khan to leave Bombay, which he did on the pretext of ill-health. But before leaving he made Mogubai aware of all that had transpired. As he took her leave, he was crying, and cursing those who would suck the vitality out of someone’. However, it was Mogubai who was deprived of all support by this incident.

Her simple mind could not fathom why she, who never wished ill of anyone, and kept to herself, should make enemies. Was it something she had done in her previous birth that was responsible for this recurring humiliation ? What could she do except blame her stars for her misfortune ? Now there was no hope. Everyone but everyone, Bashir Khan, Vilayat Khan had turned their backs on her.

She could have made a living, singing in concerts, on the basis of the little musical knowledge she had acquired. Even pedantic critics had granted her that much approval. But this was not enough to satisfy Mogubai. Her hunger hadn’t been satiated. She wanted the complete stamp of a gharana on her. She wanted to become the primary representative of that gharana and this was still a distant goal.

Years passed. One evening Mogubai sat doing riyaaz with 15 month-old Kishori on her lap, concentrating on a difficult palta as taught by Hyder KhanSaheb. She imagined Khansaheb Alladiya guiding her through the intricacies of the composition and earning his appreciation for reproducing his phrases perfectly. The fidgeting of the small child woke her from this trance. She hardly believed her eyes when she saw that it was Khansaheb Alladiya Khan in person teaching her the palta.

To her, this was an incredible turn of events; it was more like a beautiful dream. She must have pinched herself to make certain. But it wasn’t a dream, it was real, Khansaheb had returned.

After this, without any further ado, she arranged to perform the ganda-bandhan ceremony with Alladiya Khansaheb. She tried her best to repay him for the knowledge he had bestowed on her of his own accord in the past, and what’s more, hadn’t charged her anything for. Alladiya Khansaheb now taught her till the very end and at one jalsa acclaimed her as the queen among the vocalists of his gharana. This was truly a golden day in Mogubai’s life.

In yet another jalsa, Mogubai shared the platform with other disciples of Khansaheb. Connoisseurs of music commended her for her superiority and extraordinary talent. Layabhaskar Khapruji lauded her flawless sense of rhythm. Years upon years of superhuman efforts and tenacious hardwork had paid off. The promise she had made her mother had been fulfilled. This has been the tale of an uneducated woman’s zealous pursuit of music in a time that was not exactly kind to her.

Shrimati Mogubai is now known as one of India’s great singers. She also teaches music and several of her students have made a name for themselves. A chance to hear her is considered a rare bonanza by music lovers. Mogubai, by her achievements, has negated the notion that only a wealthy person can pursue the musical arts. At times, she would even drink water to quell her hunger rather than interrupt her endeavour. She got what she wanted and for which she devoted her whole life. Shy of publicity, she received less popularity than she merited. After all, fate decides how successful or popular one is. Why is one able to sell trinkets at the price of gold while another can’t sell his gold even at the price of trinkets ? That’s the way the cookie crumbles. However, wise men know the difference between a bauble and a ring of solid gold. And as long as there are wise people in this world, a person sincere about his business need not worry. He will always get the respect he deserves.

As Kesarbai Kerkar, so also Mogubai Kurdikar is a pillar of Goa’s musical tradition. Her devotion to her pursuit,music, will inspire coming generations to fearlessly face the ups and downs in their chosen occupations.

From: Kalaatm Gomantak by Gopalkrishna Bhobe

From:

Tuesday, 19 February 2019

Kesarbai Kerkar - Classic Gold 2 - Cassette released in India in 1998

Here the second volume of 78 rpm records by the great artist. As in the previous one, each track is an amazing jewel. With this our series of posts of recordings by one of the most outstanding artists of recording history is completed.

A funny thing: during our posting of these recordings the visits to our blog went down by almost 50%. For me the proof that really great artists and especially their archival recordings are not that appreciated even by visistors of our blog. I take this as a sign that I'm on the right track and will continue to post rare recordings by almost forgotten artists. Of course there will be also great artists - as in the past - who are admired by a greater public.

Saturday, 16 February 2019

Kesarbai Kerkar - Classic Gold 1 - Cassette released in India in 1998

Here the first of two volumes of 78 rpm records by the artist.

For details see:

Wednesday, 13 February 2019

Kesarbai Kerkar - Rarest of the Rare - Vol. 4 - Live - Raga Kedar

Copy of the cover of the cassette

I have two copies of this cassette, both on CD. The first is a private CD made by our friend DM in 2001. I don't know if it was made directly from the original cassette or from a copy on cassette, perhaps from the collection of James Stevenson, as two of our previous posts. The second I purchased a few years ago, also as a privately made CD, from an Indian collector. This one is about 10 minutes longer. How much it corresponds to the original cassette I don't know. If these are the two sides of one cassette merged into one track I also don't know. And there is still a question regarding a small gap around minute 44:35.

But anyway, the second seems, because of its length, the more satisfying. So we post here this one.

Sunday, 10 February 2019

Kesarbai Kerkar - Rare Live Recordings - Vol. 4 - Private CD

This is again a private CD containing this time the recordings of the cassette "Rarest of the Rare - Vol. 3", published in 1985, plus two old records: Raga Desh (1936) & Holi Kamach (1955). This CD was again made by Denis Meyer in 2000 with recordings from a cassette from the collection of James Stevenson. Many thanks to both collectors for making these precious recordings available.

As I'm not sure if the cassette "Rarest of the Rare - Vol. 3" just contained only Raga Lalita Gauri (I don't hear any trace that two sides of a cassette were merged into one track) and I have another copy of Vol. 3 containing also a Hori & Chaiti in Raga Bhairavi of similar length, which could well be the side two of that cassette, I add it here.

The order of the recordings posted here is

(ignore the track details given on the back of the CD):

1. Raga Lalita Gauri

2. Hori & Chaiti in Raga Bhairavi

3. Raga Desh (1936)

4. Holi Kamach (1955)

Note: the term Holi is often transcribed as Hori.

.

Copy of the cover of the original cassette

Thursday, 7 February 2019

Kesarbai Kerkar - Rare Live Recordings - Vol. 3 - Private CD

This is again a private CD containing this time the recordings of the cassette "Rarest of the Rare - Vol. 5 & 6", published in 1985. As we posted already the original cassette of vol. 6 we post here only the content of vol. 5. The cassette has on side 1 Raga Jaijaivanti and on side 2 first the continuation of Raga Jaijaivanti and then a Bhajan in Raga Bhairavi: Shiv Shiv Charan.

Denis Meyer, a great collector and lover of Indian music, made this CD in 2000 and was so generous to share it with a few friends. Many thanks to him.

The cassette comes from the collection of the singer Ustad Mohammad Sayeed Khan, the son of the great Sarangi master Ustad Abdul Majid Khan, who used to accompany Kesarbai Kerkar for many years.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)